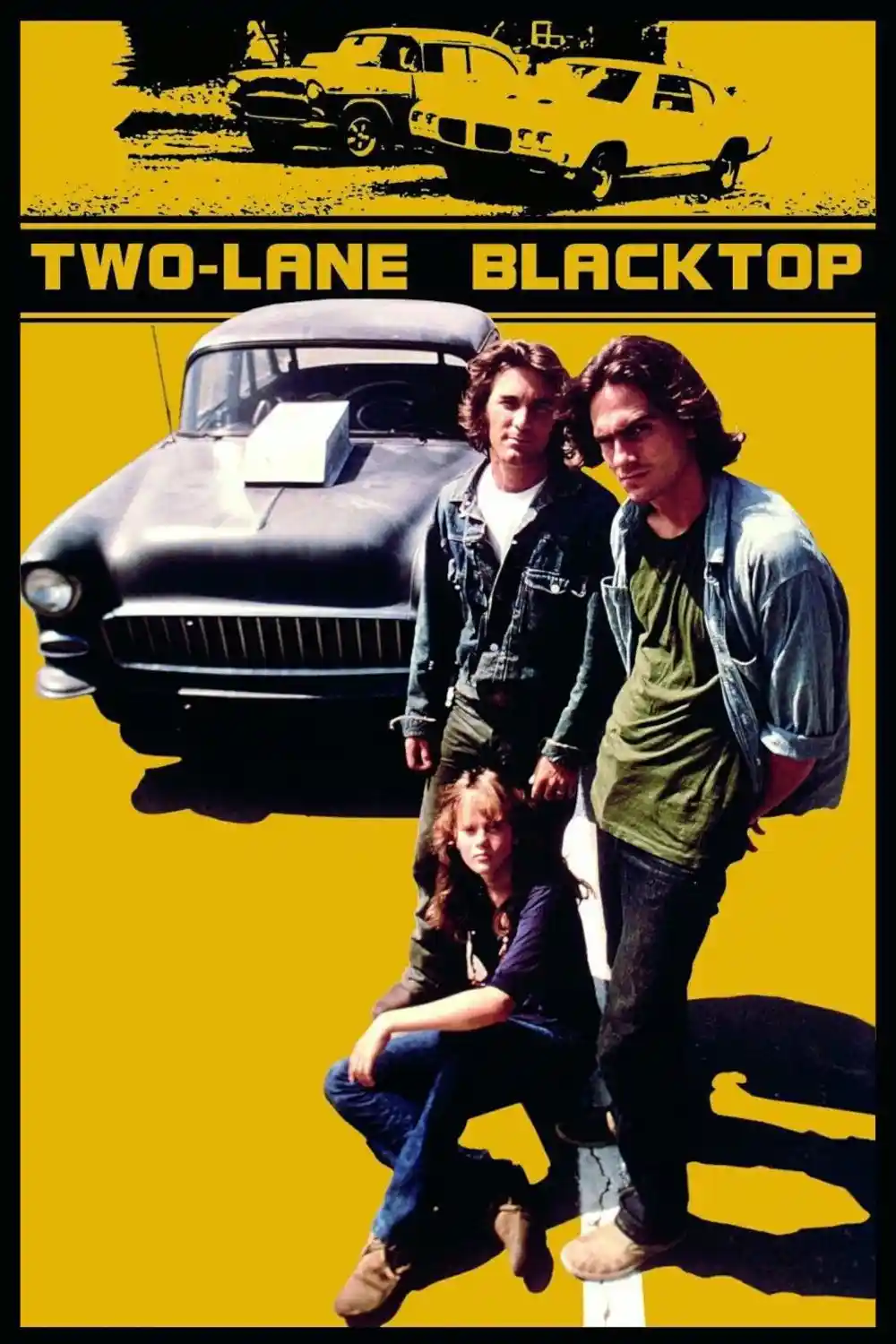

Two-Lane Blacktop (1971): The Purest American Road Movie Ever Made

Monte Hellman's existentialist drag race burns its own ending. With James Taylor, Dennis Wilson, and a '55 Chevy, this anti-narrative masterpiece defined a generation's alienation.

I need to tell you about a race that never ends. About two musicians who couldn’t act playing characters who don’t have names. About a film that Esquire magazine planned to publish as a screenplay—an unprecedented event—before it disappeared into cult obscurity. About the purest American road movie ever made.

Two-Lane Blacktop is not a film you watch for plot. It barely has one. It’s a film you watch for the hum of engines, the silence between sentences, and the gradual realization that the destination was never the point.

The Non-Story

Two men drive a primer-gray 1955 Chevy across America. They race for money, winning pink slips from people foolish enough to challenge them. They pick up a girl. They meet a man in a new GTO who wants to race them to Washington D.C., for ownership of both cars.

That’s it. That’s supposedly the plot. But Hellman has no interest in the race. Characters forget about it for long stretches. The destination keeps changing. By the end—if you can call it an end—the race has been abandoned entirely.

The characters don’t even have names. The credits list them as:

- The Driver (James Taylor)

- The Mechanic (Dennis Wilson)

- The Girl (Laurie Bird)

- GTO (Warren Oates)

They exist as functions, not people. And that’s the point.

The Anti-Easy-Rider

Two-Lane Blacktop was Universal’s attempt to capitalize on the success of Easy Rider (1969). They saw that counter-culture road movies could make money, and they commissioned this one with a substantial budget and rock star casting.

What they got was the opposite of Easy Rider in almost every way:

| Easy Rider | Two-Lane Blacktop |

|---|---|

| Clear counter-culture message | No message |

| Characters with names and backgrounds | Anonymous ciphers |

| America as enemy | America as empty space |

| Motorcycle as freedom | Car as obsession |

| Martyrdom ending | Non-ending |

| Rock soundtrack | Engine sounds |

Where Easy Rider told you what to think about America, Two-Lane Blacktop refuses to tell you anything. It presents and withholds meaning simultaneously.

James Taylor and Dennis Wilson: The Non-Actors

Here’s a production decision that shouldn’t have worked: casting two rock musicians with zero acting experience as your leads. James Taylor was at the height of his singer-songwriter fame. Dennis Wilson was the Beach Boys’ drummer, the only one who actually surfed.

Neither of them “acts” in any conventional sense. Taylor speaks in a near-monotone, rarely making eye contact. Wilson communicates mostly through grunts and mechanical actions. They seem disconnected from everything, including each other.

And it’s perfect.

Hellman understood that the blankness of his leads would register as existential emptiness, not bad acting. The Driver and The Mechanic don’t know why they race. They don’t know where they’re going. They don’t know what they want. Taylor and Wilson’s genuine discomfort in front of the camera becomes character—these are men who exist only in relation to their machine.

Warren Oates: The One Who Talks

In contrast to the silent protagonists, Warren Oates’s GTO is a compulsive storyteller. He picks up hitchhikers and tells them different lies about his life: he’s a test pilot, he’s a television producer, he won the car in Las Vegas.

GTO is a man who doesn’t exist without an audience. His car is new, flashy, powerful—but it’s also not really his in the way the Chevy belongs to Driver and Mechanic. They know their machine intimately, can hear every cylinder. GTO can barely drive.

The race between them isn’t really about speed. It’s about authenticity—or the impossibility of it. GTO invents stories to fill his emptiness. Driver and Mechanic have no stories at all. Neither approach works. Neither finds meaning.

The Girl: Drifting Between

Laurie Bird’s Girl moves between the cars, sleeping with different men, forming no permanent attachments. She’s been read as a symbol of everything from America itself to the impossibility of connection in a mobile society.

I read her more simply: she’s doing exactly what the men are doing, just without a car. She moves. She doesn’t explain why. She doesn’t arrive anywhere.

Bird would make only two more films before dying by suicide in 1979. There’s a strange poetry in her casting—another person who seemed to drift through life without finding purchase.

The Ending That Isn’t

⚠️ Spoiler Warning: Discussion of the film’s famous ending follows.

Two-Lane Blacktop doesn’t end. It stops.

The race has been forgotten. Driver and GTO have almost become friends—or whatever passes for friendship among the disconnected. The Chevy is at a drag strip. The camera watches Driver prepare to race.

And then the film literally burns.

The image slows, freezes, and the celluloid melts in the projector gate. The screen fills with white. There’s no resolution, no winner, no destination reached. The medium itself fails before the story can conclude.

Hellman has said this ending was always planned—it’s not the result of an incomplete film. It’s a deliberate statement: there is no ending to the American road. There is no arrival. There is only motion until motion stops.

Technical Observations

Hellman’s direction is precise despite the apparent formlessness:

Sound design: The film is obsessed with engine sounds. You hear every gear shift, every rev. The mechanical becomes musical.

Empty frames: Characters are frequently dwarfed by landscape. The American highway system is presented as beautiful and meaningless—infinite asphalt leading nowhere.

Natural lighting: No Hollywood gloss. Gas stations look like gas stations. Diners look like diners. There’s a documentary quality to the surfaces.

Dialogue overlap: Characters speak over each other, don’t finish sentences, communicate through shared silences. It feels real in a way most scripted dialogue doesn’t.

The Esquire Moment

Before the film’s release, Esquire magazine announced they would publish Rudy Wurlitzer’s screenplay in full—an unprecedented event that was supposed to build anticipation. The issue was printed. The film flopped. Universal pulled it from theaters almost immediately.

For decades, Two-Lane Blacktop existed mainly as legend: the screenplay people had read, the film almost nobody had seen. It became a cult object through its absence.

When it was finally re-released on DVD in the 2000s, it found its audience: people who recognized that the emptiness wasn’t a failure but a feature. The film had been waiting for viewers who understood that sometimes the American Dream is just a road going somewhere else.

My Rating: 8.5/10

What works:

- The casting transforms non-acting into aesthetic

- Warren Oates is brilliant as the desperate mythmaker

- Sound design makes the car into a character

- The ending is genuinely audacious

- Captures early-70s alienation perfectly

What doesn’t:

- Will frustrate anyone wanting narrative satisfaction

- The pace is deliberately alienating

- Some viewers will find the blankness merely boring

If You Liked This, Try:

- Vanishing Point (1971) — More conventional but similarly nihilistic road film

- Paris, Texas (1984) — Wenders channeling American emptiness

- Badlands (1973) — Malick’s beautiful, detached criminals on the road

- Stranger Than Paradise (1984) — Jarmusch’s low-key American drift

- Electra Glide in Blue (1973) — Motorcycle cop in the existentialist desert

Two-Lane Blacktop asks a question it refuses to answer: what are we racing toward? The Driver doesn’t know. The Mechanic doesn’t know. GTO invents answers because the truth is unbearable: there’s nothing at the end of the road except more road.

Richard Linklater called it “the purest American road movie.” He was right. It’s pure because it’s empty. It’s American because emptiness is our condition. The race continues until the film itself can’t anymore.

Keep driving. There’s nowhere else to go.

References

- Wurlitzer, Rudy. Screenplay, Esquire Magazine, 1971

- Linklater, Richard. “Two-Lane Blacktop introduction,” Criterion Collection

- Hoberman, J. “Easy Rider vs. Two-Lane Blacktop,” Village Voice, 1999

- Taylor, James. Interview, Rolling Stone, 1971

- Hellman, Monte. Commentary track, Criterion Blu-ray