The Godfather Trilogy: An Enduring Legacy of Power, Family, and Tragedy

From Marlon Brando's iconic Don Corleone to Al Pacino's descent into darkness, the Godfather trilogy redefined American cinema. A deep dive into what makes these films eternal masterpieces.

“I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse.”

Fifty years later, that line still carries weight. Not because it’s clever—it’s actually rather simple—but because of everything behind it. The quiet menace. The absolute certainty. The understanding that power, real power, doesn’t need to raise its voice.

The Godfather trilogy represents something rare in cinema: a sustained artistic achievement across three films that somehow manages to be both commercially successful and genuinely profound. These aren’t just gangster movies. They’re American Shakespeare—epic tragedies dressed in pinstripe suits and fedoras.

The Making of a Masterpiece

The first Godfather almost didn’t happen. Not the way we know it, anyway.

Paramount wanted a cheap, quick exploitation film. They considered hiring a television director and casting Danny Thomas as Don Corleone. Francis Ford Coppola was their last choice—a young filmmaker known for small art films who seemed entirely wrong for a commercial project.

Coppola fought for everything. He fought to cast Marlon Brando, whom the studio considered washed up and difficult. He fought to cast the unknown Al Pacino as Michael, when the studio wanted Robert Redford or Ryan O’Neal. He fought to shoot on location in New York and Sicily. He fought to make the film a period piece rather than a contemporary story.

He won every battle, and in doing so, created a template for how serious filmmakers could work within the studio system. The Godfather proved that artistic ambition and commercial success weren’t mutually exclusive—a lesson Hollywood has been selectively remembering and forgetting ever since.

Brando’s Don: Power in Stillness

Marlon Brando’s Vito Corleone remains one of cinema’s most influential performances, and it works through radical restraint.

Watch how little Brando moves. In a medium that rewards big gestures, he does almost nothing. His hands rest. His body stays planted. Even his famous raspy voice—achieved by stuffing cotton in his cheeks—forces him to speak slowly, deliberately, as if every word costs something.

This physical containment creates the impression of enormous power held in check. Vito doesn’t need to prove anything. His reputation precedes him. When he does act—the horse’s head, the revenge for Sonny—the violence is shocking precisely because the stillness that surrounds it is so complete.

Brando improvised many of his most memorable moments. The cat he strokes in the opening scene wasn’t scripted—it wandered onto set and he incorporated it. The gesture perfectly captures the character: tenderness and menace intertwined, a man who can be gentle with small things while orchestrating terrible acts.

Michael’s Arc: The Tragedy at the Center

If Vito is the trilogy’s gravitational center, Michael is its protagonist—and his journey from war hero to soulless crime lord constitutes one of cinema’s great tragedies.

In the first film’s opening, Michael sits apart from his family. He wears his Marine uniform. He tells Kay about his father’s business with detachment, assuring her “that’s my family, Kay. It’s not me.” This is Michael’s tragedy in miniature: he believes he can remain separate from what he comes from.

The restaurant scene, where Michael kills Sollozzo and McCluskey, marks the point of no return. Coppola films it with excruciating tension—the subway noise, Michael’s sweating face, the gun hidden in the bathroom. When the shots finally come, they’re brutal and awkward. This isn’t a glamorous movie killing. It’s ugly, desperate, and transformative.

By the first film’s end, Michael has become his father. The famous closing shot—the door closing on Kay as Michael receives his capos’ obeisance—visualizes what the narrative has accomplished. The man who wanted to be different has become exactly what he swore to reject.

The second film deepens this tragedy by showing us Vito’s origin alongside Michael’s present. The parallel structure isn’t just clever—it’s thematically devastating. We see Vito becoming a criminal out of necessity, protecting his family and community. We see Michael becoming a monster out of choice, sacrificing his family to protect his power.

By the third film, Michael is alone. His wife has left him. His children are estranged. His attempts at legitimacy have failed. The man who once had everything has lost everything that matters, and the film’s operatic climax—his daughter’s death—completes the punishment he’s been earning across three movies.

The Godfather Part II: The Perfect Sequel

Most sequels diminish their predecessors. The Godfather Part II somehow enhances the original while standing as a masterpiece in its own right.

The dual timeline structure was revolutionary. We follow young Vito’s immigration to America and rise to power alongside Michael’s expansion of the family business and destruction of his soul. The two stories comment on each other without ever directly intersecting, creating meaning through juxtaposition rather than connection.

Robert De Niro’s young Vito is a remarkable act of creative channeling. He doesn’t imitate Brando—the physical differences make that impossible—but he captures something essential about the character: the intelligence, the patience, the capacity for both warmth and ruthlessness. De Niro won an Oscar for largely silent work, communicating Vito’s development through physicality and expression.

The film’s famous ending—Michael sitting alone by the lake, remembering a birthday party from before the war—achieves something remarkable. We see Michael as he was: young, optimistic, announcing his intention to enlist. His brothers mock him. His father enters. And we understand, in this moment of past happiness, exactly how much Michael has lost.

There’s no dialogue in the final shot. Just Michael’s face, weathered and empty, remembering what he destroyed. It’s one of cinema’s great endings because it trusts the audience to feel the weight of everything that came before.

Part III: The Redemption That Couldn’t Be

The Godfather Part III has a complicated reputation. Released sixteen years after Part II, it couldn’t possibly match the first two films—and it doesn’t. But viewed on its own terms, it’s more interesting than its reputation suggests.

The film’s central question—can Michael Corleone find redemption?—is genuinely compelling. Michael is old now, suffering from diabetes, desperate to make his family legitimate. He donates millions to the Church. He tries to extract himself from the criminal world that defined him.

But the past won’t release him. Old enemies resurface. Old sins demand payment. The attempt to go straight leads, through Byzantine Vatican politics and family betrayals, to the worst tragedy of all: the death of Mary Corleone on the steps of the opera house.

Sofia Coppola’s performance as Mary has been widely criticized, often unfairly. The role is underwritten, and she lacks the training that professional actors bring. But the emotional reality of the final scene—Mary dying in her father’s arms, Michael’s silent scream—transcends whatever limitations came before.

Francis Ford Coppola released a re-edited version in 2020, titled “Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone.” The changes are mostly structural, and while they improve certain aspects, they don’t fundamentally alter the film’s strengths or weaknesses. Part III remains a flawed conclusion to an almost-perfect trilogy.

Gordon Willis: Painting with Darkness

The visual language of the Godfather films is inseparable from cinematographer Gordon Willis, whose work earned him the nickname “Prince of Darkness.”

Willis lit the films in ways that violated every rule of conventional cinematography. Faces disappear into shadow. Entire scenes play in darkness broken only by shafts of light. The opening shot—Don Corleone’s face emerging from black—establishes a visual approach that persists through all three films.

This wasn’t just stylistic flourish. The darkness serves the narrative. These are men who operate in shadows, whose true natures are hidden, whose power depends on what remains unseen. Willis’s lighting makes this visible—or rather, invisible in exactly the right ways.

The famous orange motif—oranges appear before deaths throughout the trilogy—demonstrates how carefully the visual elements were considered. It’s not symbolism in any heavy-handed sense; it’s pattern, recurring imagery that accumulates meaning through repetition.

Nino Rota’s Score: The Sound of Tragedy

Try to imagine The Godfather without its music. You can’t, because Nino Rota’s score has become inseparable from the films themselves.

The main theme—that melancholy trumpet melody—achieves something paradoxical. It’s beautiful, even romantic, yet it accompanies terrible events. This isn’t ironic counterpoint; it’s something more sophisticated. The music suggests how the characters see themselves, the dignity and tragedy they believe their lives contain.

Rota drew on Sicilian folk traditions, but he filtered them through his own sensibility. The result sounds simultaneously authentic and artificial—like a memory of music rather than music itself. It’s perfect for films about people constructing mythologies around their own violence.

The love theme, used primarily for Michael and Kay, carries its own tragedy. Each time it recurs, the relationship it represents has deteriorated further. By Part III, when the theme plays, it sounds less like romance than requiem.

The Family: Coppola’s Real Subject

For all the violence and crime, The Godfather trilogy is fundamentally about family—its bonds, its betrayals, its inescapable claims.

The Corleones are recognizable as a family even as they do terrible things. They argue at dinner tables. They worry about their children. They celebrate weddings and mourn deaths. Coppola, drawing on his own Italian-American background, grounds the operatic drama in domestic reality.

This is what distinguishes The Godfather from lesser crime films. We don’t just watch the Corleones commit crimes; we watch them live. We see the texture of their daily existence—the food, the music, the rituals. When violence intrudes, it feels like violation precisely because normalcy has been so thoroughly established.

The women of the trilogy deserve particular attention. Kay, Connie, Apollonia, Mary—they’re not protagonists, but they’re not decorative either. They witness what the men do. They suffer consequences. They make choices within the constraints available to them. Kay’s final confrontation with Michael in Part II—“It was an abortion, Michael”—constitutes one of the trilogy’s most devastating moments.

Why These Films Endure

The Godfather trilogy has influenced virtually every crime narrative that followed—The Sopranos, Goodfellas, countless imitators. But influence doesn’t explain why the films themselves remain powerful.

They endure because they work on multiple levels simultaneously. As genre entertainment, they deliver memorable characters, quotable dialogue, and satisfying narrative mechanics. As American mythology, they interrogate the immigrant experience, the promise and corruption of capitalism, the price of power. As tragedy, they trace an inexorable decline from hope to destruction.

They endure because Coppola and his collaborators took the material seriously without taking it solemnly. The films have humor, warmth, and beauty alongside their darkness. They understand that monsters can love their children, that evil can be banal, that tragedy is measured not in body counts but in spiritual costs.

Most of all, they endure because they’re about something universal dressed in something specific. The Corleones are particular—Italian-American, criminal, bound by specific codes and circumstances. But their struggles—between duty and desire, family and self, power and morality—belong to everyone.

Fifty years from now, someone will watch Don Corleone receive supplicants in his darkened office. They’ll watch Michael close the door on Kay. They’ll watch an old man scream silently over his daughter’s body. And they’ll understand, as we understand, that some stories never stop being told.

My Rating:

- The Godfather: 10/10

- The Godfather Part II: 10/10

- The Godfather Part III: 7.5/10

If you love this trilogy:

- Goodfellas (1990) - Scorsese’s visceral counterpoint

- The Sopranos (1999-2007) - The Godfather’s television heir

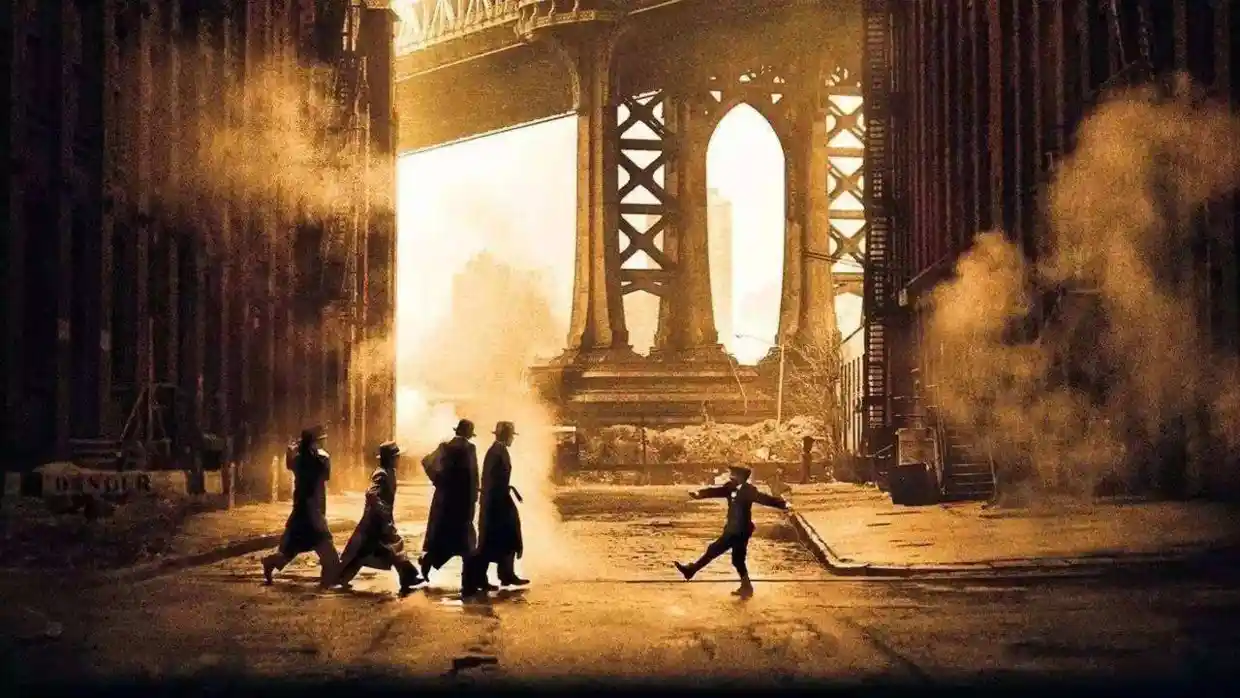

- Once Upon a Time in America (1984) - Another immigrant crime epic

- Heat (1995) - Mann’s modern crime masterpiece