Once Upon a Time in America: Leone's Requiem for the American Dream

Sergio Leone's 1984 epic took 15 years to make and was butchered by studios. The restored version reveals one of cinema's most ambitious meditations on memory, betrayal, and the cost of the American Dream.

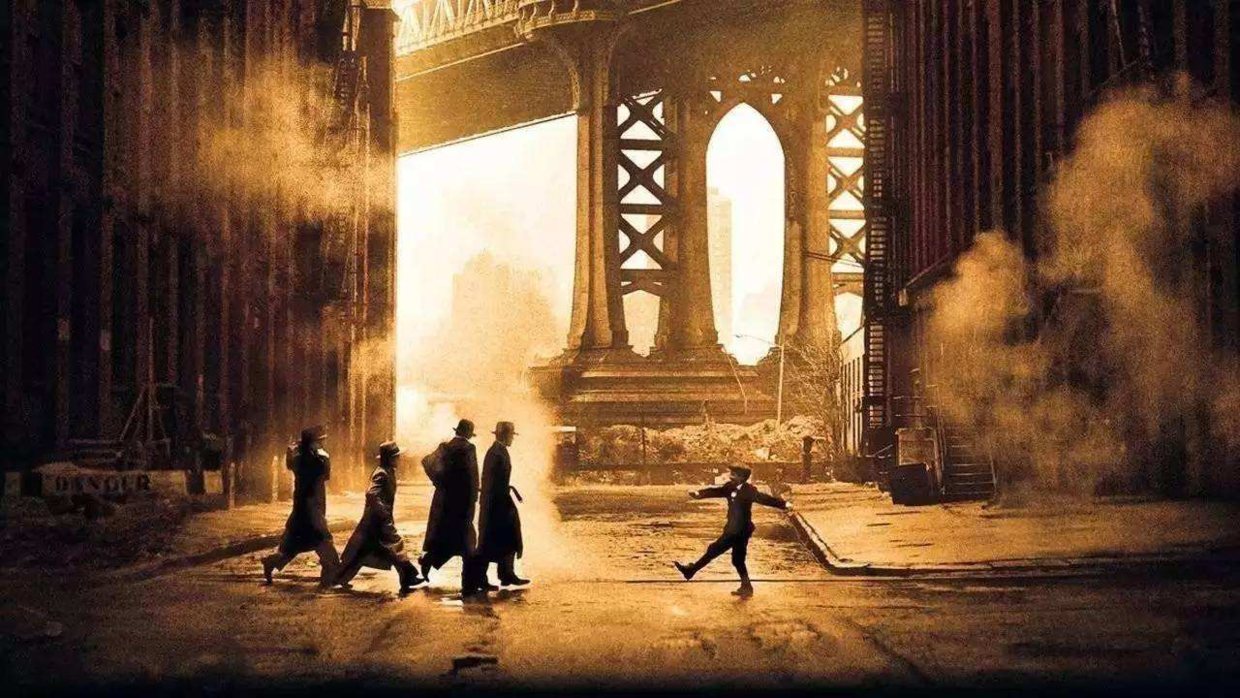

The shot you’re probably picturing right now—silhouettes moving through golden dust under the Manhattan Bridge, Ennio Morricone’s haunting score swelling on the soundtrack—doesn’t appear until deep into the film. But it’s become the image that defines Once Upon a Time in America, and for good reason.

In a single composition, Sergio Leone captures everything his film is about: figures moving through a dream space that’s neither quite past nor present, beauty emerging from industrial decay, the sepia-toned mythology of an America that never existed except in immigrant imaginations.

This is Leone’s masterpiece. It’s also one of cinema’s great tragedies—a film that was mutilated on release, misunderstood for decades, and only now receiving the recognition it deserves.

Fifteen Years in the Making

Leone spent the 1960s and early 70s revolutionizing the Western with his Dollars trilogy and Once Upon a Time in the West. By the mid-70s, he was ready to move on. He’d been offered The Godfather but turned it down—he wanted to make his own American crime epic, something more personal and ambitious than anything he’d attempted before.

The project consumed fifteen years of his life.

Leone developed the screenplay through countless drafts, obsessing over every detail of Jewish immigrant life in early 20th century New York. He compiled thousands of photographs, interviewed survivors of that era, and constructed an elaborate mythology of the Lower East Side that blended historical research with pure operatic imagination.

When filming finally began in 1982, Leone shot over ten hours of footage. His original cut ran nearly six hours. The version he reluctantly trimmed for theatrical release was 229 minutes—still one of the longest mainstream American films ever made.

Then the studio panicked.

The Butchering

Warner Bros. looked at Leone’s sprawling, non-linear meditation on time and memory and saw commercial suicide. They recut the film to 139 minutes, eliminating the complex flashback structure and arranging events in chronological order.

The result was incomprehensible. Characters appeared and disappeared without explanation. Emotional payoffs arrived before their setups. The entire philosophical architecture of the film collapsed into meaningless noise.

Critics savaged it. Audiences ignored it. Leone, who had spent fifteen years crafting his vision, watched it die in a single weekend.

He never made another film. He died five years later, preparing a project about the siege of Leningrad that would never be completed. Once Upon a Time in America killed him—not literally, but spiritually. The failure broke something that couldn’t be repaired.

The Restoration

It took decades, but the film has been restored to something approaching Leone’s vision. The 229-minute cut is now standard, and an even longer 269-minute version has surfaced, incorporating additional scenes that deepen the narrative.

Watching the restored film, you understand immediately what the studio destroyed. This isn’t a gangster movie with flashbacks. It’s a meditation on memory itself, structured like consciousness rather than plot.

The film moves between three time periods—1920s childhood, 1930s young adulthood, and 1968 old age—but not in any orderly fashion. We drift between eras following emotional logic rather than chronology. A sound, a smell, a half-remembered face triggers transitions. The past isn’t something that happened; it’s something that’s always happening, bleeding into the present, reshaping itself with each recollection.

This structure isn’t decorative. It’s the entire point. Once Upon a Time in America is a film about how we construct our lives retrospectively, how memory selects and distorts, how the stories we tell ourselves become more real than what actually occurred.

Noodles and Max: A Friendship as Epic

At the center of everything is the relationship between Noodles (Robert De Niro) and Max (James Woods)—two Jewish kids from the Lower East Side who build a criminal empire together, destroy each other, and remain bound by a love neither can escape or acknowledge.

De Niro gives one of his greatest performances, and it’s almost entirely interior. Noodles is a man who has retreated so far into himself that his face reveals almost nothing. We watch him watching, remembering, piecing together a past that may or may not have happened the way he recalls. The performance requires us to read silences, to interpret glances, to construct psychology from absence.

Woods matches him with something completely different—an energy that’s almost manic, a hunger that can never be satisfied. Max wants everything: money, power, respect, legitimacy. He’s the engine of the plot, the one who pushes their small-time operation toward empire. But there’s a desperation underneath the ambition, a need for Noodles’ approval that he can never admit.

Their relationship is the American Dream in microcosm. Two immigrants who believe the myth—that anyone can rise, that success is available to those who seize it—and discover that the dream was always a trap. What they build together destroys them both.

The Opium Den Frame

The film begins and ends in an opium den, with Noodles seeking oblivion after betraying his friends. This frame is crucial and often misunderstood.

One interpretation holds that everything we see—the 1968 sequences, the revelation about Max’s fate, the final confrontation—is an opium dream. Noodles never left that den. He’s been lying there for thirty-five years, constructing an elaborate fantasy of reunion and resolution that reality never provided.

The evidence for this reading is substantial. The 1968 sequences have a dreamlike quality, with impossible coincidences and theatrical confrontations. The final shot—Noodles smiling enigmatically in the opium den—suggests satisfaction rather than grief, as if he’s just experienced something pleasant rather than the devastating revelations the film has shown us.

Leone never confirmed or denied this interpretation. He wanted the ambiguity. The question isn’t whether the events “really happened” but what it means that Noodles needs them to have happened. What story does he tell himself to survive?

The Women Problem

Let’s address the elephant in the room: the film’s treatment of women is deeply problematic.

The central female character, Deborah (Elizabeth McGovern), exists primarily as an object of Noodles’ obsession. Their relationship culminates in a rape scene that the film treats with disturbing ambiguity—horrifying, yet shot with Leone’s characteristic visual poetry, set to Morricone’s romantic score.

This is difficult to defend and impossible to ignore. Leone’s vision of masculinity is operatic but also toxic, romanticizing a violence toward women that the film never adequately critiques. The female characters have no interiority; they exist only in relation to male desire.

You can acknowledge this failure while still engaging with what the film accomplishes elsewhere. Art doesn’t have to be morally pure to be meaningful. But the gender politics of Once Upon a Time in America remain a serious flaw that limits its achievement.

Morricone’s Score: Memory Made Music

No discussion of this film is complete without addressing Ennio Morricone’s score—arguably the greatest of his legendary career.

The main theme, built around pan flute and wordless vocals, sounds like memory itself: distant, melancholic, impossibly beautiful. It plays during transitions between time periods, suggesting that music is the medium through which Noodles accesses his past.

But Morricone does something more sophisticated than simply providing emotional wallpaper. He creates themes that transform depending on context. A melody that sounds romantic in one scene becomes sinister in another. The same musical phrase accompanies both innocence and corruption, suggesting that they’re inseparable—that the seeds of destruction were always present in the moments of grace.

The “Deborah’s Theme” is particularly devastating. It’s one of the most beautiful pieces of film music ever written, and it accompanies scenes of obsession, violation, and loss. The beauty doesn’t excuse the ugliness; it implicates us in it. We’re seduced by the same romanticism that blinds Noodles to his own monstrosity.

The Manhattan Bridge Shot

Let’s return to that iconic image: silhouettes under the Manhattan Bridge, golden light filtering through dust, the geometry of urban infrastructure transformed into something cathedral-like.

Leone shot this scene at magic hour, when the sun sits low enough to create that particular amber glow. The figures are deliberately arranged to suggest both movement and timelessness—they’re walking somewhere, but they could be walking forever. The bridge frames them like a proscenium arch, making the street into a stage.

This is Leone’s cinema in miniature: the transformation of mundane reality into myth through composition, light, and music. The Lower East Side wasn’t actually this beautiful. But Leone isn’t documenting reality; he’s showing us how memory beautifies the past, how nostalgia transforms poverty into poetry.

The shot lasts only seconds in the film, but it contains the entire project. This is what America looked like to immigrants who believed in it—not as it was, but as it felt, as they needed it to be.

The Ending: Garbage Truck or Transcendence?

The film’s final sequence remains one of cinema’s most debated endings.

After the confrontation with Max in 1968, Noodles walks out into the night. A garbage truck passes—an anachronistic vehicle that seems to belong to a later era. As it moves down the street, we hear strange sounds: laughter, music, something that might be celebration.

Cut to the opium den. Noodles smiles. The end.

What does it mean? Some argue the garbage truck is carrying Max’s body, that Noodles has witnessed his friend’s suicide and now returns to the oblivion of the opium den. Others suggest the garbage truck represents the disposal of the past itself—all those memories, all that history, being carted away like trash.

The most haunting interpretation: none of this happened. The garbage truck, like everything else in the 1968 sequences, is a fantasy. Noodles never left the opium den. He’s been dreaming for thirty-five years, and the smile is the smile of someone lost in a pleasant illusion, never to wake up.

Leone cuts to black before giving us answers. The ambiguity is the point. Once Upon a Time in America is a film about the stories we tell ourselves, and it refuses to distinguish between truth and necessary fiction.

Why This Film Matters

Once Upon a Time in America is flawed, excessive, and morally troubled. It’s also one of the most ambitious films ever made—a genuine attempt to capture how memory works, how identity is constructed, how the American Dream seduces and destroys.

Leone spent fifteen years on this film because he understood it was his final statement. Everything he knew about cinema—composition, music, pacing, the operatic enlargement of human emotion—he poured into this project. The result is imperfect but irreplaceable.

The studio version that killed his career is now a footnote. The restored film has taken its place among the great achievements of cinema. Leone didn’t live to see his reputation rehabilitated, but his work survives, and it’s as powerful today as it was forty years ago.

Once upon a time in America, there was a dream. Leone shows us that dream in all its beauty and horror, and asks us to consider what it cost.

My Rating: 9.5/10

Strengths: Unprecedented ambition, career-best performances, Morricone’s transcendent score, visual poetry Weaknesses: Deeply problematic treatment of female characters, some pacing issues even in restored version

Essential companion viewing:

- Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) - Leone’s Western masterpiece

- The Godfather Part II (1974) - The other great immigrant crime epic

- Goodfellas (1990) - Scorsese’s more visceral approach to similar material

- The Irishman (2019) - De Niro returns to similar themes decades later