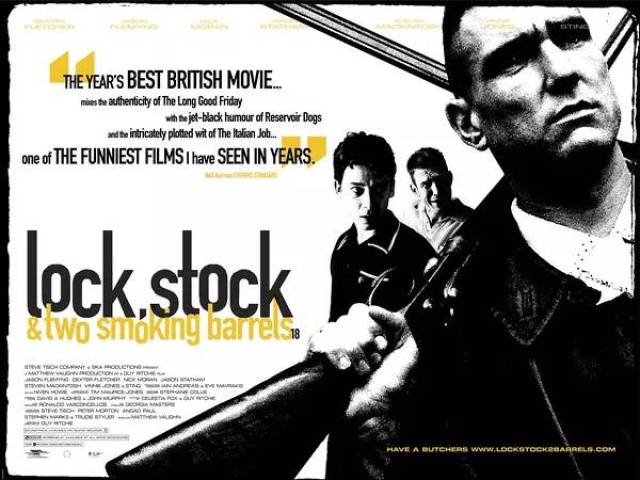

Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels: How Guy Ritchie Reinvented British Crime Cinema

Guy Ritchie's 1998 debut exploded onto screens with razor-sharp dialogue, labyrinthine plotting, and a visual style that spawned countless imitators. Why this cockney crime caper remains the gold standard for British gangster films.

Before Guy Ritchie made Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, British gangster films had a certain respectability to them. They were grim, realistic affairs—The Long Good Friday, Get Carter, Mona Lisa—films that treated organized crime as serious business deserving serious treatment.

Then this hyperactive, motor-mouthed, impossibly stylish debut came along and blew the whole genre wide open. Suddenly, gangsters could be funny. Violence could be slapstick. And a labyrinthine plot involving debt collectors, marijuana growers, antique shotguns, and incompetent thieves could feel like the most exhilarating thing cinema had produced in years.

Lock, Stock didn’t just launch Guy Ritchie’s career. It created a template that British crime films—and their American imitators—have been following ever since.

Four Lads and a Card Game

The setup is deceptively simple. Four friends from London’s East End pool their money to enter a high-stakes card game run by “Hatchet” Harry, a porn mogul with anger issues and a rigged deck. Eddie, the card sharp of the group, loses spectacularly. They now owe Harry half a million pounds, payable in one week.

What follows is controlled chaos.

To pay off the debt, the lads decide to rob their neighbors—a crew of small-time criminals who are themselves planning to rob a marijuana grow operation. But the grow operation belongs to a much bigger fish. And the guns they acquire for the robbery have their own complicated history. And Harry has his own plans involving Eddie’s father’s bar.

Every thread connects to every other thread. Characters who seem peripheral become essential. Coincidences pile up until they stop feeling like coincidences and start feeling like fate—or farce, depending on your perspective.

The Ritchie Style: Invented Here

Watch the first five minutes of Lock, Stock and you’ll see techniques that have since become clichés—but in 1998, they felt genuinely new.

The freeze-frames with character introductions. The speed-ramping during action sequences. The split-screens. The chapter titles. The way the camera pushes in on faces during moments of revelation. The snap zooms. The whip pans.

Ritchie didn’t invent all of these techniques, but he synthesized them into something coherent and distinctly his own. The visual language of Lock, Stock is dense, restless, and unapologetically flashy—matching the energy of its characters and the complexity of its plot.

There’s a sequence where Nick the Greek explains a deal gone wrong, and Ritchie visualizes the story with cutaways, freeze-frames, and satirical captions. It’s showing off, pure and simple. But it’s showing off in service of storytelling, making exposition feel kinetic rather than boring.

Every choice reinforces the film’s worldview: that crime is absurd, that plans always go wrong, and that the universe has a dark sense of humor about human ambition.

The Dialogue: Poetry of the Streets

“It’s been emotional.”

“A minute ago this was the safest job in the world. Now it’s turning into a bad day in Bosnia.”

“The entire British Empire was built on cups of tea… and if you think I’m going to war without one, you’re mistaken.”

Ritchie’s dialogue crackles with wit, profanity, and cockney slang so thick that American audiences needed subtitles. The characters speak in a heightened register—nobody actually talks like this—but it feels authentic because it’s internally consistent. This is how people would talk if life were written by someone very clever.

The verbal sparring matches the visual pyrotechnics. Characters don’t just explain things; they perform explanations. Monologues become set pieces. Even throwaway lines have a precision that rewards repeat viewing.

What makes it work is the specificity. These aren’t generic tough guys spouting generic tough-guy dialogue. They’re products of a particular time and place—late 90s London, where old-school East End culture was colliding with new money and changing demographics. The film captures a moment that was already passing.

The Ensemble: Before They Were Famous

Lock, Stock is a showcase for actors who would soon become much more famous—and a reminder that stardom isn’t always predictable.

Jason Statham plays Bacon, the group’s streetwise hustler. He’s magnetic but not yet polished—you can see the raw charisma that would make him an action star, but it’s unrefined, more authentic for being rough around the edges. This was before the Transporter franchise, before he became a brand. Here he’s just a guy from London playing a guy from London.

Vinnie Jones, the footballer-turned-actor, plays Big Chris—a debt collector with a code of honor and a young son he brings along on jobs. Jones has exactly one expression and approximately three line readings, but it doesn’t matter. His physical presence does the work. He would never become a great actor, but he became an effective one, and this film established the template.

The four leads—Nick Moran, Jason Flemyng, Dexter Fletcher, and Statham—have genuine chemistry. They feel like actual friends, not actors pretending to be friends. When they argue, scheme, and panic, we believe the relationships.

The Structure: Chaos With a Blueprint

The plot of Lock, Stock is famously convoluted, but here’s the thing: it’s not actually confusing. Ritchie maintains clarity through sheer craft.

Every scene establishes exactly what we need to know for the next scene. Character relationships are sketched efficiently—sometimes a single line tells us everything. When the various plot threads start converging, we understand the collisions because we’ve been carefully prepared.

This is harder than it looks. Most films attempting this multi-strand structure end up muddled, with audiences losing track of who wants what and why it matters. Ritchie never loses control. The chaos is an illusion; underneath it, the architecture is rock solid.

The film builds to a shootout where nearly every character converges in one location, each with their own agenda, none aware of what the others are planning. It should be a mess. Instead, it’s a masterclass in staging and editing—funny, violent, and perfectly timed.

Violence as Slapstick

Lock, Stock is a violent film, but it treats violence as comedy rather than tragedy.

People get hit with dildos. A traffic warden is brutalized for giving out parking tickets. Criminals stumble through botched robberies like characters in a Buster Keaton film. The body count is significant, but death rarely feels real—it’s too stylized, too cartoonish, too perfectly timed for punchlines.

This approach has drawn criticism. By making violence funny, doesn’t the film trivialize it? Doesn’t it aestheticize criminality in ways that are morally questionable?

These are fair points, and they apply to the entire genre Ritchie helped create. But the counterargument is that Lock, Stock never pretends to be realistic. It’s a fairy tale about crooks, a heightened fantasy where the normal rules of consequence don’t apply. We’re not meant to take it seriously as a depiction of criminal life. We’re meant to enjoy it as a ride.

Whether that defense satisfies probably depends on your tolerance for aesthetic violence in general.

The Shotguns: A Macguffin with Character

The “two smoking barrels” of the title refer to a pair of antique shotguns—valuable weapons with a complicated provenance that various characters spend the film trying to acquire.

Ritchie uses the shotguns as a classic Macguffin: an object everyone wants, whose actual importance matters less than the conflicts it generates. But he also gives the guns personality. We learn their history, see them change hands, watch them accidentally discharge at comically inappropriate moments.

By the film’s end, the shotguns have become characters in their own right—silent witnesses to the chaos they’ve caused, beautiful objects that bring out the ugliness in everyone who covets them.

The final shot of the film—which I won’t spoil—involves the shotguns in a way that’s both hilarious and structurally perfect. It’s the kind of ending that makes you want to immediately rewatch the entire film to appreciate how carefully it was set up.

The Influence: Everybody’s Doing It

Lock, Stock’s success spawned an industry.

Guy Ritchie himself went on to make Snatch, essentially the same film with bigger stars and a tighter runtime. Other filmmakers rushed to replicate the formula: quick cuts, freeze-frames, interlocking crime plots, cockney characters, ironic violence. Layer Cake, RocknRolla, The Gentlemen—the template remains surprisingly durable.

Across the Atlantic, the influence merged with Tarantino’s similar innovations to create a whole subgenre of hyperkinetic crime comedy. Everybody wanted that Lock, Stock energy—the sense that crime was fun, that dialogue could be stylized, that plot complexity was a feature rather than a bug.

Most imitators missed what made the original work. They copied the techniques without understanding the craft underneath. Lock, Stock isn’t successful because of its style; it’s successful because the style serves the story. Remove the foundation, keep only the flourishes, and you get empty exercises in coolness.

The Soundtrack: Eclectic and Essential

Ritchie’s music choices are as distinctive as his visual style—a mix of obscure soul, reggae, and rock that feels both period-specific and timeless.

The opening credits play over “Hundred Mile High City” by Ocean Colour Scene, immediately establishing a swagger that carries through the entire film. Other tracks—James Brown, Dusty Springfield, Stone Roses—create a sonic landscape that’s distinctly British while drawing on American influences.

Music cues are used precisely, often for ironic counterpoint. Brutal scenes play against cheerful songs. Moments of triumph are undercut by melancholic choices. The soundtrack isn’t just accompaniment; it’s commentary.

Why It Still Works

Twenty-five years later, Lock, Stock hasn’t dated as badly as you might expect.

Some of the cultural references are obscure now. The technology—or lack thereof—marks it as pre-smartphone. Certain attitudes feel of their time in ways that might make modern audiences uncomfortable.

But the filmmaking remains sharp. The performances are still fun. The plot still satisfies. And the energy—that relentless, confident, showing-off energy—still feels exciting rather than exhausting.

Part of this is simply quality: good craft ages better than trendy craft. But part of it is that Lock, Stock captures something timeless about male friendship, criminal ambition, and the tendency of elaborate plans to collapse spectacularly.

The film knows that life is absurd. It knows that confidence is usually misplaced. It knows that the universe loves a good joke at human expense. These truths don’t expire.

The Legacy

Guy Ritchie went on to a strange career—Madonna marriage, Sherlock Holmes blockbusters, Disney’s Aladdin remake—but Lock, Stock remains his purest statement. Before success complicated things, before budgets expanded and ambitions diffused, he made exactly the film he wanted to make.

It’s rough in places. The gender politics are nonexistent (women barely appear and have nothing to do). The morality is flexible to the point of meaninglessness. These are legitimate criticisms.

But as a pure entertainment, as a showcase for a distinctive directorial voice, as a snapshot of a moment in British culture—Lock, Stock delivers. It’s been emotional.

My Rating: 8.5/10

Strengths: Innovative visual style, crackling dialogue, intricate plotting, perfect ensemble chemistry Weaknesses: Essentially no female characters, style occasionally overwhelms substance

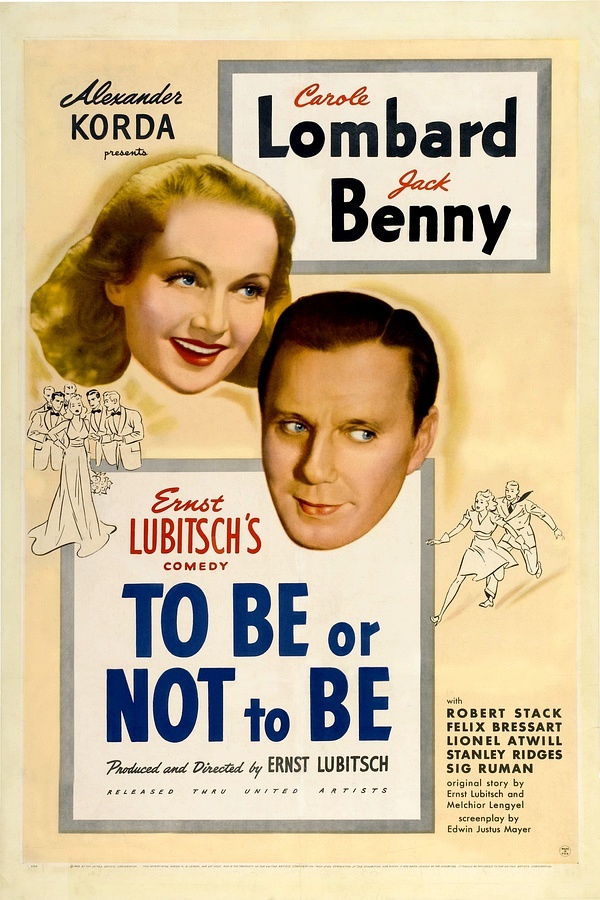

If you enjoyed this, also watch:

- Snatch (2000) - Ritchie’s refined version of the same formula

- In Bruges (2008) - Dark comedy with British criminals abroad

- The Guard (2011) - Irish spin on the crime comedy genre

- Layer Cake (2004) - Sleeker, more serious British crime