Rewatching The Shawshank Redemption: 8 Details You Probably Missed

After 30 years, The Shawshank Redemption remains IMDb's top-rated film. But how many of these hidden details, symbolic choices, and production secrets did you actually catch? A deep dive into Frank Darabont's masterpiece.

I’ve seen The Shawshank Redemption at least a dozen times. Maybe more. Like most people, I thought I knew this film inside out—the hope, the friendship, the escape, the reunion on that beach in Zihuatanejo.

Then I read the original novella. Then I watched the director’s commentary. Then I fell down a rabbit hole of production history and deleted scenes.

Turns out I barely knew this movie at all.

1. Morgan Freeman Almost Wasn’t Red

Here’s something that sounds like Hollywood legend but is actually true: Morgan Freeman got the role of Red during one of the most turbulent moments in American history.

The Los Angeles riots of 1992 had just erupted. The city was burning. And somewhere in the chaos of that moment, the casting decision was made to give Freeman the role originally written for a middle-aged Irish guy named “Red” Redding—a character whose nickname, in Stephen King’s novella, is explicitly explained as coming from his red hair.

Freeman’s casting changed everything. Not just because of his extraordinary performance, but because it transformed the film’s thematic weight. A story about two prisoners became a story about two men from completely different worlds finding common ground. The racial dynamics are never explicitly addressed in the film, and that’s precisely what makes them so powerful.

Darabont kept one winking reference to the original character. When Andy asks Red why he’s called Red, Freeman delivers that perfect deadpan: “Maybe it’s because I’m Irish.”

That single line carries thirty years of Hollywood history in it.

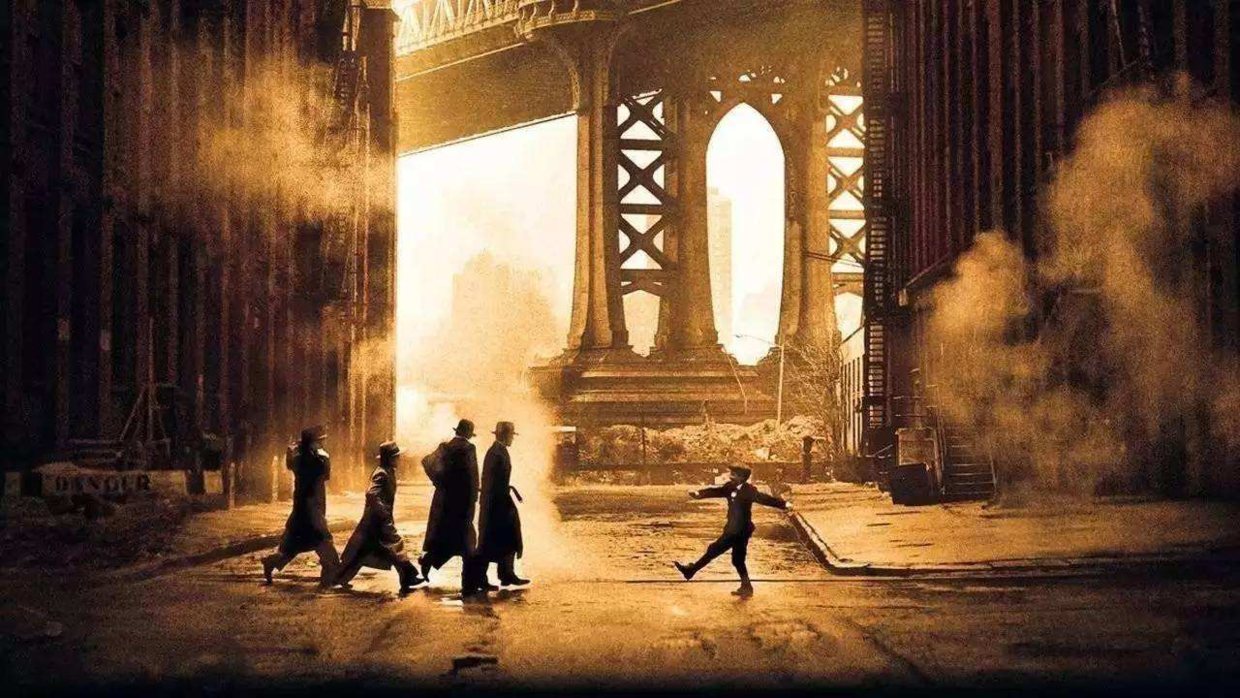

2. The Ohio State Reformatory: A Character in Itself

Most films use locations as backdrops. Shawshank uses its location as a co-star.

The Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield wasn’t just convenient—it was essential. Built in 1886, the prison had been closed for decades when Darabont’s team arrived. The decay was real. The oppressive architecture was real. That sense of institutional weight pressing down on every frame? You can’t fake that.

Walk through the actual building today (it’s now a museum and tourist destination, thanks largely to this film), and you’ll understand something that doesn’t fully translate on screen: the scale of the place is overwhelming. The cell blocks stretch upward like gothic cathedrals. The walls seem to absorb sound and light.

Darabont shot the film in sequence as much as possible, partly for performance reasons, but also because the building itself seemed to demand a certain kind of respect. You don’t just waltz into a place with that much history and start rearranging the furniture.

3. The Tragedy of “Fat Ass”

Let’s talk about the character nobody wants to talk about.

The prisoner nicknamed “Fat Ass”—the one who breaks down crying on his first night and gets beaten to death by Captain Hadley—appears on screen for maybe three minutes. He has no real name in the film. He exists solely to die.

And that’s exactly the point.

His death serves a brutal narrative function: it establishes the stakes. It shows us what Shawshank does to people who can’t adapt. But look closer at how Darabont frames this sequence, and you’ll notice something uncomfortable.

The other prisoners bet on who will crack first. They make a game of it. Red participates. Our protagonist, our moral center, our narrator—he gambles on another man’s psychological breakdown for cigarettes.

This is the first of many moments where the film refuses to let its characters (or its audience) off the hook. Red isn’t a saint. He’s a man who has learned to survive by becoming somewhat monstrous himself. His eventual redemption means something precisely because we’ve seen what he was capable of becoming.

4. The Unspoken Horror

The film handles prison rape with a sophistication that was unusual for 1994 and remains rare today.

The “Sisters” and their leader Bogs are terrifying not because the film sensationalizes their violence, but because it refuses to. We never see the actual assaults. We see the aftermath—Andy’s bruised face, his careful movements, his slow-building rage.

What makes this handling so effective is what it implies about the institution itself. The guards know. The warden knows. Everyone knows. And nothing is done about it until Andy makes himself useful to the power structure—at which point Bogs is suddenly transferred and beaten into a wheelchair.

The message is clear and damning: in this system, protection is transactional. Safety is a privilege that must be purchased, not a right that is guaranteed. Andy survives not because the institution protects the innocent, but because he learns to make himself valuable to the corrupt.

This is not a heartwarming message. The film buries it under more palatable themes of hope and friendship, but it’s there, waiting for anyone willing to look.

5. Where Are the Women?

The Shawshank Redemption is almost entirely male. The few women who appear—Andy’s wife, the woman she’s having an affair with, Rita Hayworth on a poster—exist primarily as objects or obstacles.

This isn’t an oversight. It’s a choice, and it’s worth examining.

Prison films have always struggled with gender. The all-male environment creates a narrative space where traditional masculine values—loyalty, stoicism, physical endurance—can be explored without the “complication” of female perspectives. Some critics have argued this makes such films inherently limited. Others suggest the absence of women allows for a different kind of emotional honesty between male characters.

What’s interesting about Shawshank is how it positions women symbolically. Rita Hayworth, Marilyn Monroe, Raquel Welch—the posters that hide Andy’s tunnel represent idealized femininity, but also represent escape itself. The women are literally doorways to freedom.

Is this progressive? Probably not. Is it interesting? Absolutely. The film uses the male gaze in ways that are worth unpacking, even if the unpacking makes us uncomfortable.

6. Mozart’s “Duettino”: The Sound of Transcendence

The scene where Andy locks himself in the warden’s office and plays Mozart’s “Sull’aria” over the prison loudspeakers is one of cinema’s great moments. But why that particular piece of music?

“The Marriage of Figaro” is an opera about servants outwitting their masters. It’s about the powerless finding ways to assert their dignity against those who control them. The duet Andy plays—“Sull’aria…che soave zeffiretto”—features two women plotting together, using beauty and intelligence to subvert male authority.

Darabont knew exactly what he was doing.

The prisoners stand in the yard, frozen, listening to something they don’t understand but feel in their bones. Red’s narration tells us he never found out what those Italian ladies were singing about, and he didn’t want to know. Some things, he says, are best left unspoken.

But the choice of music speaks for itself. In a film about men trapped in a system designed to break them, the sound of liberation comes from women singing about resistance. The gendered politics of the film are complicated, but in this moment, something breaks through.

7. Andy as Christ Figure

Religious imagery saturates The Shawshank Redemption, mostly through the hypocritical warden who quotes scripture while running his corrupt empire. But the film’s real theological statement is made through Andy himself.

Consider: Andy is an innocent man who suffers for crimes he didn’t commit. He endures years of torment. He offers hope and education to those around him. He literally emerges from filth and darkness into light and freedom—a baptismal rebirth through the prison sewage pipe.

The Christ parallels are obvious once you start looking. Andy even assumes a cruciform pose in the rain after his escape, arms spread wide, face lifted to the sky.

But here’s what makes it interesting: Andy isn’t passive. He doesn’t turn the other cheek. He spends twenty years planning an elaborate revenge against his captors, and when he finally escapes, he destroys them utterly—exposing the warden’s corruption, stealing his money, sending the whole rotten system crashing down.

This is Christ as action hero. Redemption through meticulous planning and righteous fury. It’s a very American interpretation of salvation, and it resonates for reasons that probably say more about us than about the film.

8. The Dream That Was Never Shot

Here’s something most fans don’t know: Darabont wrote a scene that would have changed the entire ending of the film.

In the original script, after Andy’s escape, there was a dream sequence. Red, still in prison, imagines finding Andy dead on the beach—a body washed up by the tide, the dream of Zihuatanejo revealed as just another prison fantasy, another hope that dies.

Darabont wrote it. He planned to shoot it. Then he decided not to.

In interviews, he explained that as a director, he realized the scene had no narrative function. It would have introduced doubt where the film needed certainty. The audience needs to believe that Andy makes it, that the beach is real, that hope is justified.

But knowing that scene existed—knowing Darabont considered undermining his own happy ending—changes how you watch the film. The famous final scene, where Red walks across the sand toward Andy, suddenly carries a shadow of the alternative. What if it isn’t real? What if Red is just imagining what he needs to survive?

The film doesn’t answer this question. It doesn’t have to. The beauty of the ending lies precisely in its refusal to confirm or deny. Hope, the film suggests, isn’t about certainty. It’s about choosing to believe anyway.

The Ending Nobody Agrees On

Speaking of that ending—did you know it almost didn’t exist?

Darabont’s original cut ended with Red on the bus, heading toward the Mexican border, his fate uncertain. Test audiences hated it. They wanted resolution. They needed to see the reunion.

So Darabont shot the beach scene. And then spent the next thirty years answering questions about whether it was a mistake.

Some purists argue the bus ending is superior—more ambiguous, more true to the film’s themes about hope versus certainty. The beach scene, they say, is too neat, too Hollywood, too easy.

Others argue the beach scene is earned. After two and a half hours of suffering and struggle, the audience deserves catharsis. Red deserves catharsis. Denying it would be punishing the viewer for caring.

I’ve gone back and forth on this for years. These days, I think the beach ending works because of how it’s shot—those long, wide frames that keep the two men small against the vastness of ocean and sky. Even in triumph, even in reunion, there’s something fragile about the image. Two tiny figures on an infinite beach, finally free but somehow still dwarfed by the world around them.

Maybe that’s the real message. Freedom isn’t a destination. It’s just a bigger prison with better views.

My Rating: 10/10

Strengths: Perfect performances, layered symbolism, emotional authenticity Weaknesses: Honestly? I can’t think of any that matter.

If you loved this film, also watch:

- The Green Mile - Another Darabont/King collaboration

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest - The spiritual predecessor

- Cool Hand Luke - Paul Newman in the definitive prison rebel role

- A Prophet - The French masterpiece about institutional survival