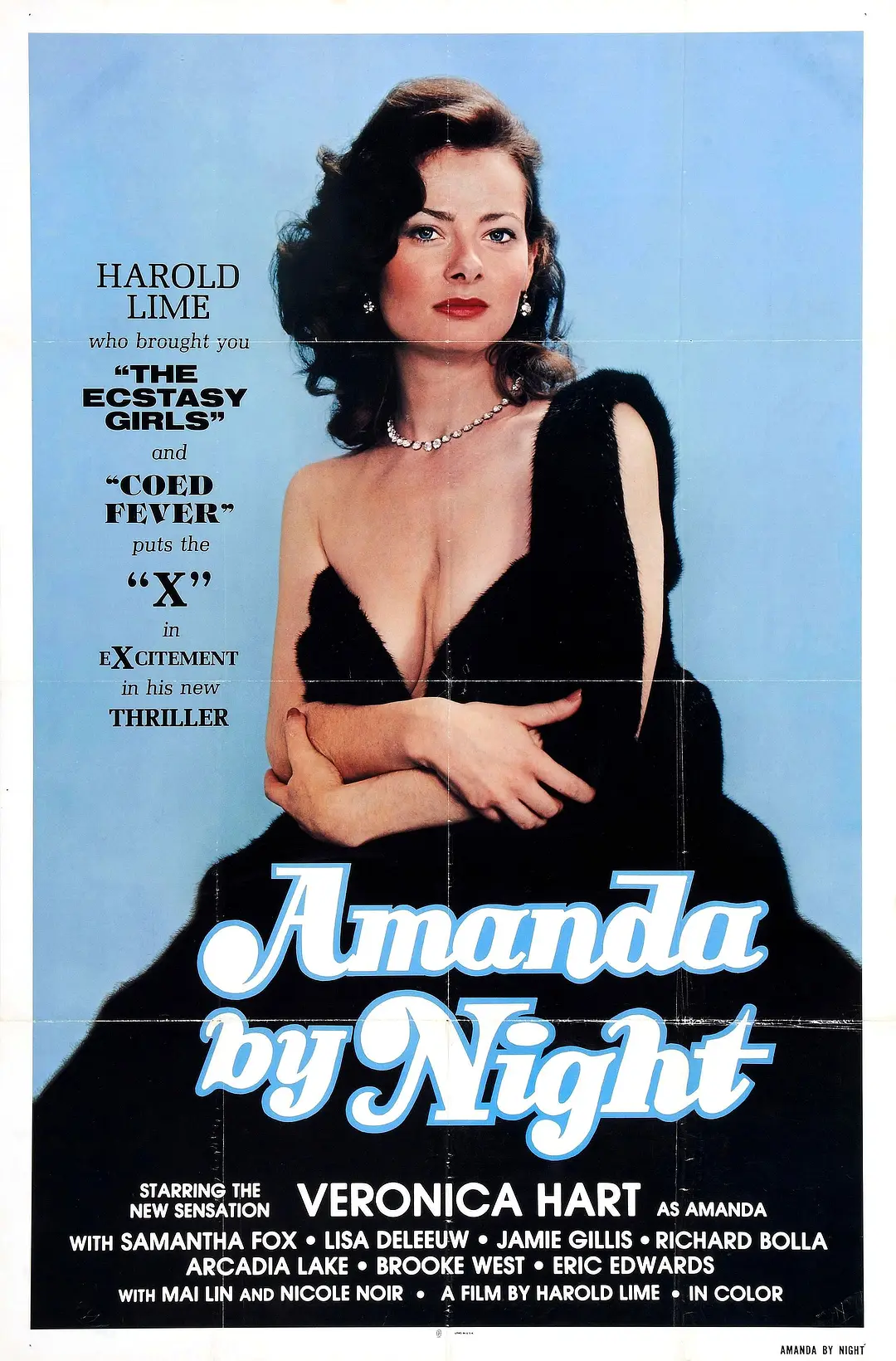

The Night Amanda (1981): Finding Light in the Darkest Corners

A deep dive into Gary Graver's forgotten 1981 crime thriller about a sex worker seeking justice. How this exploitation-era film delivers unexpected moral clarity and challenges our assumptions about genre cinema.

There’s a line from the Chinese poet Gu Cheng that keeps circling in my head whenever I think about this film: “The night gave me black eyes, yet I use them to seek light.”

That sentiment—finding moral clarity in the darkest possible circumstances—sits at the heart of Gary Graver’s 1981 crime thriller The Night Amanda. It’s a film that most cinephiles have never heard of, buried in the avalanche of exploitation cinema that defined the era. But dig it up, dust it off, and you’ll find something unexpectedly resonant.

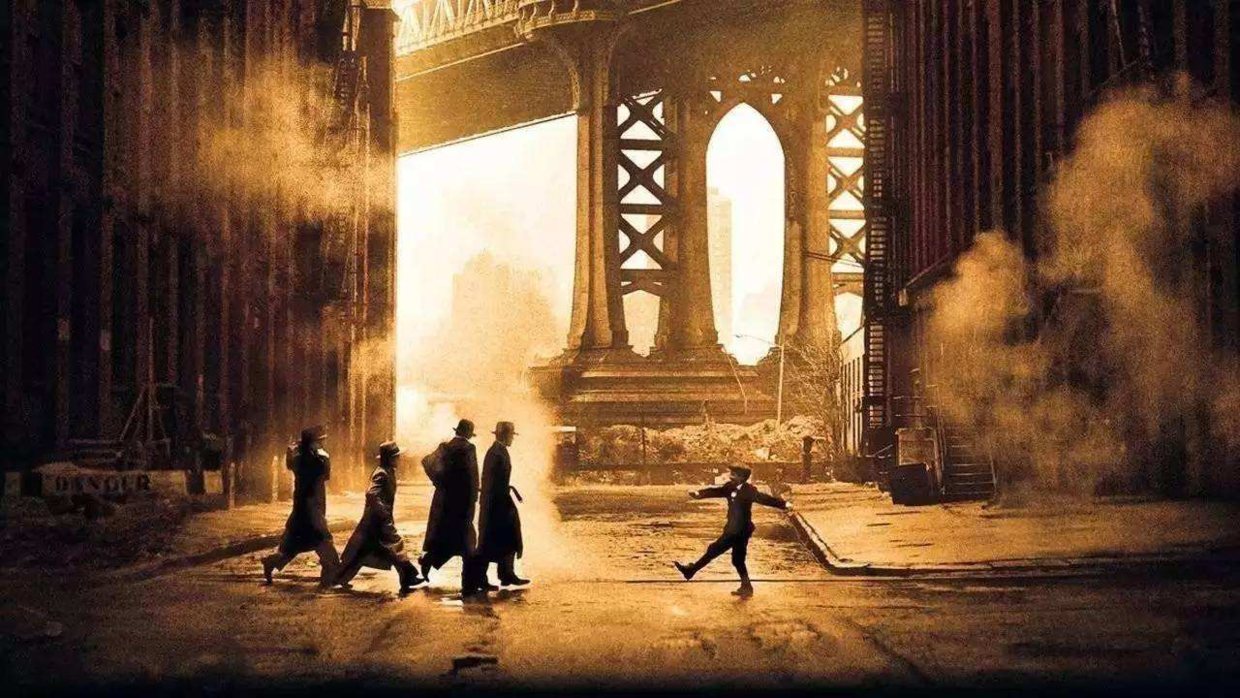

The Setup: Sin City Before Sin City

Amanda Heath works the high end of a profession the world pretends doesn’t exist. She’s not a streetwalker—she’s expensive, selective, and smart. In the opening scenes, Graver establishes her world with clinical precision: the hotels, the clients, the careful maintenance of boundaries between transaction and emotion.

Then a young woman turns up dead. Another sex worker, barely out of her teens. The police investigation is perfunctory at best, corrupt at worst. Nobody cares when women like her die. They’re invisible in life and forgotten in death.

Amanda decides to care.

What follows isn’t quite a revenge thriller, though it borrows those mechanics. It’s something stranger and more interesting—a moral reckoning that forces Amanda to confront not just the men who killed her friend, but the entire system that made such a killing possible. And inevitable.

Gary Graver: The Cinematographer Who Directed

Here’s something that changes how you watch this film: Gary Graver spent most of his career as a cinematographer, working with everyone from Orson Welles to exploitation king Roger Corman. When he stepped behind the director’s chair, he brought an eye for composition that most B-movie directors couldn’t dream of.

Watch how he frames Amanda in doorways and windows throughout the film. She’s constantly positioned at thresholds—between inside and outside, between her public persona and private self, between the world she inhabits and the one she’s trying to expose. It’s visual storytelling that elevates the material beyond its budget.

There’s a shot about forty minutes in that still haunts me. Amanda stands at a rain-streaked window, city lights blurred behind her, and for just a moment, Graver holds on her reflection rather than her face. We see her seeing herself. The effect is disorienting, almost Bergman-esque. What’s a shot like that doing in an exploitation film?

That’s the question The Night Amanda keeps asking, and never quite answering.

The Performance Nobody Saw

I won’t pretend the acting across the board is stellar. This is 1981 exploitation cinema—some performers are clearly here for the paycheck, delivering lines like they’re reading a grocery list. But at the center of it all, there’s something genuinely compelling happening.

Amanda doesn’t play victim. She doesn’t play hero either. What comes across, scene after scene, is a woman who has made a series of pragmatic choices to survive in a world that offers her limited options. She’s not ashamed of her work, but she’s not proud of it either. She simply does it, the way a coal miner mines coal or a teacher teaches classes. It’s labor, and she treats it as such.

This matter-of-fact approach to sex work was radical in 1981 and, honestly, remains radical today. Most films either glamorize the profession or condemn it. The Night Amanda does neither. It simply observes, and in that observation, grants its protagonist a dignity that moralizing would deny.

When Amanda begins her investigation, she doesn’t transform into someone else. She uses the skills she already has—reading people, navigating dangerous men, knowing when to reveal information and when to withhold it. Her profession hasn’t damaged her ability to seek justice. It’s equipped her for it.

The System as Antagonist

Here’s where the film gets genuinely subversive.

The men who killed the young woman aren’t monsters. They’re businessmen, politicians, police officers—pillars of the community who happen to have appetites they’d rather keep hidden. When Amanda starts pulling threads, she discovers the predictable web of corruption: payoffs, cover-ups, mutual protection among the powerful.

But Graver isn’t interested in the mechanics of conspiracy. He’s interested in how systems of exploitation perpetuate themselves. The killer isn’t one man. The killer is an entire structure that designates certain people as disposable and then acts surprised when they get disposed of.

There’s a scene where Amanda confronts a detective who’s clearly been paid to look the other way. She doesn’t threaten him or appeal to his conscience. She simply asks: “When you go home tonight, what do you tell yourself?”

He doesn’t answer. The film cuts to his face, and Graver holds the shot for an uncomfortable beat. We watch him not answering. The silence says everything.

Violence and Its Consequences

The Night Amanda isn’t a bloodless film. There’s violence here, some of it ugly. But unlike many exploitation films of the era, the violence has weight. When Amanda hurts someone, we see what that costs her. When someone hurts Amanda, we see the damage linger beyond the scene.

This might seem like basic filmmaking, but in the context of early ’80s genre cinema, it’s practically revolutionary. The standard approach treated violence as spectacle—bodies as props, injuries as entertainment. Graver’s camera refuses that approach. Every act of violence in this film is treated as a moral event, something that changes the people involved.

By the final act, Amanda has blood on her hands. The film doesn’t pretend otherwise. She’s made choices that can’t be unmade, crossed lines that don’t uncross. When justice finally arrives—and it does, after a fashion—it doesn’t feel triumphant. It feels exhausted. Necessary, but exhausting.

This, too, feels honest in ways the genre rarely allowed itself to be.

The Night as Metaphor

Graver keeps returning to images of darkness throughout the film. Nighttime streets, unlit hallways, shadows that swallow faces. This is standard noir vocabulary, of course. But there’s something more specific happening.

The night in this film represents the space where society’s rules break down. It’s where transactions happen that daylight can’t acknowledge. It’s where the men who run the world come to satisfy appetites they’ve learned to hide. For Amanda, the night is both workplace and battlefield.

But the film refuses to let darkness be purely negative. There’s freedom in the night too. Away from the surveillance of respectable society, Amanda can be fully herself—not the version she performs for clients or police or judgmental strangers. The night gives her anonymity, and anonymity gives her power.

“The night gave me black eyes, yet I use them to seek light.”

Amanda’s ability to navigate darkness is precisely what allows her to expose what happens there. She’s not corrupted by her environment. She’s educated by it. And that education becomes her weapon.

The Ending Nobody Expected

I won’t spoil specifics, but the film’s conclusion wrong-foots expectations in a way that still feels daring.

Most exploitation revenge narratives end with catharsis. The wronged party achieves vengeance, the bad guys die spectacularly, order is restored. The audience leaves satisfied, the moral ledger balanced.

The Night Amanda offers something messier. Justice happens, but it’s incomplete. Some guilty parties escape. Some innocent people suffer. Amanda survives, but she’s changed in ways the film doesn’t pretend are entirely positive. The final shot finds her walking away from the camera, into a city that looks exactly as corrupt as it did at the beginning.

This isn’t nihilism. It’s realism. The systems that allowed one young woman to die will allow others to die too. Amanda has won a battle, but the war is endless. She knows it. The film knows it. And in that acknowledgment, there’s something more honest than a thousand triumphant endings.

Why This Film Matters Now

I found The Night Amanda while researching exploitation cinema of the early Reagan era. I expected sleaze. I found something that complicated my assumptions about what genre films could accomplish.

We’re in a cultural moment where discussions of sex work, systemic corruption, and the disposability of marginalized people have never been more urgent. This forty-year-old film, made for drive-ins and grindhouses, has more to say about these topics than most prestige dramas.

That’s not an argument for the film’s artistic perfection. The Night Amanda is rough around its edges, limited by its budget, occasionally clumsy in its execution. But its moral vision is clear and uncompromising. It asks who gets to count as human in our society, and who gets treated as collateral damage. It asks what justice looks like when the systems meant to provide it are themselves corrupt.

It doesn’t offer easy answers. It offers Amanda, walking into the night, using those black eyes to seek whatever light she can find.

Sometimes that’s enough.

My Rating: 7.5/10

Strengths: Graver’s visual sophistication, moral complexity rare for the genre, genuine respect for its protagonist Weaknesses: Uneven supporting performances, pacing drags in the second act, some dated elements

If this intrigues you, also explore:

- Hardcore (1979) - Paul Schrader’s underworld descent

- Ms. 45 (1981) - Abel Ferrara’s feminist revenge classic

- Klute (1971) - The prestige version of similar themes

- Nighthawks (1981) - Another nocturnal thriller from the same year