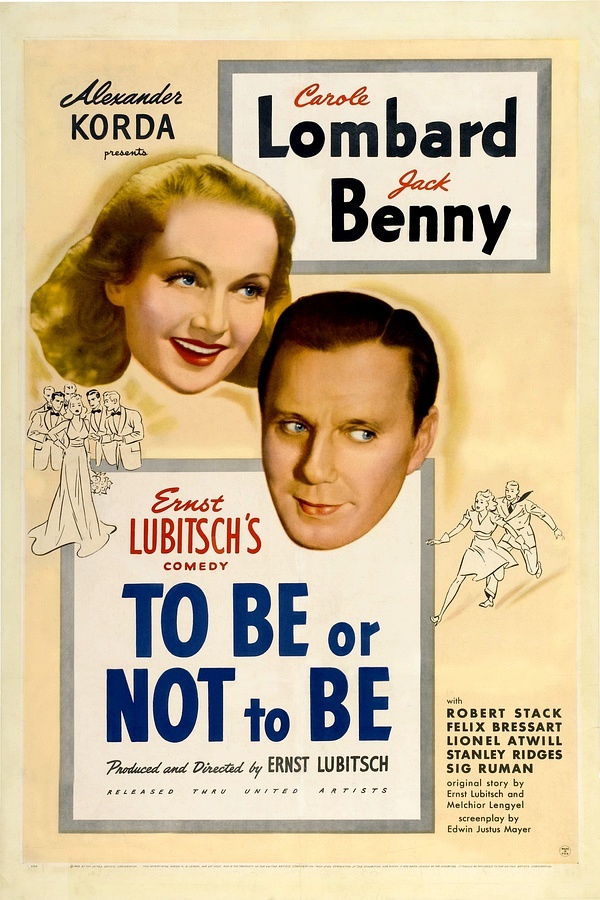

To Be or Not to Be (1942): Lubitsch's Dangerous Comedy Masterpiece

Ernst Lubitsch's audacious 1942 satire dared to make Hitler funny. How this wartime comedy about a Polish theater troupe became one of cinema's greatest achievements—and Carole Lombard's tragic final performance.

In 1942, while Nazi Germany occupied most of Europe and the outcome of World War II remained terrifyingly uncertain, Ernst Lubitsch made a comedy about Hitler.

Not just any comedy. A farce. A screwball masterpiece where actors impersonate Nazis, where the Gestapo becomes a punchline, where the fate of the Polish resistance hinges on an egomaniacal ham actor’s wounded pride about a bad review.

Critics were appalled. How dare he? How could anyone laugh at fascism while fascism was winning?

Eighty years later, To Be or Not to Be stands as one of the greatest films ever made. And its central question—can comedy confront evil?—has never been more relevant.

The Lubitsch Touch Meets the Third Reich

Ernst Lubitsch had already defined sophisticated Hollywood comedy by 1942. His “touch”—that ineffable quality of wit, elegance, and sexual sophistication—had produced masterpieces like Trouble in Paradise, Ninotchka, and The Shop Around the Corner. He was the director other directors envied.

But To Be or Not to Be was different. This wasn’t continental romance or sparkling innuendo. This was occupied Poland. Concentration camps. The systematic murder of an entire people.

Lubitsch, himself a German Jew who had fled Europe, knew exactly what he was doing. And he did it anyway.

The film opens with Hitler walking down a Warsaw street. Impossible, of course—except it’s not Hitler at all, but an actor named Bronski playing Hitler in a theatrical production. The audience’s shock becomes the film’s first joke, and also its thesis: appearance and reality are unreliable. Performance is survival. And sometimes the only way to fight monsters is to turn them into clowns.

The Plot: Theatrical Chaos as Resistance

The story follows a Warsaw theater troupe led by the magnificently vain Joseph Tura (Jack Benny) and his wife Maria (Carole Lombard), the company’s leading lady. When the Germans invade, the actors must use their theatrical skills to outwit the Gestapo, impersonate Nazi officers, and help a young Polish pilot escape to England with crucial intelligence.

On paper, it sounds like a straightforward wartime thriller. In execution, it’s something far stranger and more wonderful.

The resistance plot keeps getting derailed by the actors’ egos. Joseph Tura is less concerned about the fate of Poland than about his wife’s possible affair with a handsome pilot. His signature line from Hamlet—“To be or not to be”—becomes the signal for the pilot to leave the audience and meet Maria backstage, meaning Tura’s greatest theatrical moment is consistently interrupted by a man walking out.

This wounded vanity drives Tura to increasingly reckless acts of heroism. He impersonates a Gestapo colonel not primarily to save Poland, but to prove he’s a better actor than his rivals give him credit for. His performance is so convincing that even real Nazis are fooled—and so absurdly theatrical that we never forget we’re watching a performance within a performance.

Carole Lombard’s Final Bow

There’s no way to discuss this film without acknowledging the tragedy that shadows it.

Carole Lombard was one of Hollywood’s brightest stars—a comedic actress of extraordinary range who could match wit with anyone on screen. Her Maria Tura is sharp, beautiful, and completely in control, playing both the Nazis and her jealous husband with effortless sophistication.

Shortly after completing the film, Lombard died in a plane crash while returning from a war bond tour. She was 33 years old. To Be or Not to Be became her final performance, released posthumously to audiences who knew they were watching a ghost.

This knowledge adds an unbearable poignancy to certain scenes. When Maria walks through the ruins of Warsaw, when she faces down Nazi officers with nothing but her wits, when she and Joseph share their last reconciliation—we’re watching a woman who would be dead before the film premiered.

Lubitsch reportedly said he would never have made the film had he known what would happen. But the film exists, and Lombard’s luminous presence in it feels less like a tragedy than a kind of immortality. She left us laughing at fascism, which seems exactly right.

The Controversial Comedy of Cruelty

Not everyone appreciated the joke.

When To Be or Not to Be was released, some critics found it offensive, even obscene. The New York Times called it “callous and macabre.” How could Lubitsch make light of genuine horror? How could audiences laugh while people were dying in the very situations being parodied?

These are fair questions, and Lubitsch had answers.

The film never denies the reality of Nazi evil. The concentration camps are mentioned explicitly. Characters die. The threat is genuine and presented as such. What Lubitsch refuses to do is grant the Nazis dignity.

Consider the character of Colonel Ehrhardt, the Gestapo chief. He’s pompous, vain, and spectacularly stupid—a buffoon who fancies himself a mastermind. Every scene he’s in deflates Nazi pretension. When Joseph Tura, impersonating a fellow Nazi, makes a joke about Ehrhardt being called “Concentration Camp Ehrhardt,” the colonel laughs delightedly, pleased by his own terrible reputation.

This is the Lubitsch touch applied to genocide: make the perpetrators ridiculous without making their crimes seem small. Show them as petty, insecure men hiding behind uniforms and ideology. Strip away the mythology of power and reveal the frightened egotists underneath.

It’s a delicate balance, and Lubitsch maintains it perfectly. We laugh at the Nazis, but we never forget what they represent.

Performance as Resistance

The film’s deepest theme is the relationship between acting and survival.

In occupied Poland, everyone performs. The actors perform resistance by performing collaboration. They pretend to be Nazis to undermine actual Nazis. Their theatrical skills—the ability to inhabit a role, to maintain a fiction under pressure, to read an audience—become tools of survival.

But the film suggests something more radical: that performance might be a form of moral resistance in itself.

When Joseph Tura plays a Nazi, he’s not just fooling enemies. He’s demonstrating that fascist authority is itself a performance—a costume, a set of gestures, a script that anyone could recite. The Nazis derive power from appearing powerful. By mimicking that appearance successfully, Tura exposes its artificiality.

There’s a remarkable scene where Tura, disguised as Colonel Ehrhardt, must improvise his way through an interrogation with the real Ehrhardt’s staff. He doesn’t know the protocols, the passwords, the bureaucratic details. So he plays the role bigger—more imperious, more arbitrary, more terrifying. And it works, because fascist authority is essentially theatrical anyway.

The staff defer not to credentials they’ve verified but to the performance they recognize. They’ve been trained to respond to certain signals of dominance, and Tura provides those signals. The system that oppresses them also makes them easy to fool.

The “Heil Hitler” Running Gag

One of the film’s most audacious choices is to turn “Heil Hitler” into a comedy bit.

Throughout the film, characters constantly interrupt each other with the salute. It becomes absurd through repetition—a tic, a reflex, a meaningless noise that bureaucrats make at each other. The solemnity of the gesture is punctured every time someone has to stop mid-sentence to perform it.

In one scene, an actor impersonating Hitler receives his own salute and must figure out how to respond. Does Hitler “Heil Hitler” himself? The logical absurdity of fascist ritual becomes impossible to ignore.

This might seem like a small detail, but it’s central to what the film accomplishes. By making the salute ridiculous, Lubitsch inoculates audiences against its power. You can’t watch To Be or Not to Be and ever take “Heil Hitler” seriously again. The film vaccinates you with laughter.

Why This Film Matters Now

We live in an age of resurgent authoritarianism, rising nationalism, and political movements that depend on theatrical displays of strength. The question Lubitsch posed in 1942—can comedy puncture fascism?—has become urgent again.

Some argue that mockery is inadequate, that laughing at authoritarians trivializes their danger. Others insist that ridicule is essential, that refusing to take tyrants seriously undermines their psychological hold.

To Be or Not to Be suggests a more nuanced answer: comedy can coexist with moral clarity. You can laugh at evil and fight it simultaneously. The actors in the film are never confused about the stakes—they know they could be killed at any moment. But they choose performance over despair, wit over resignation.

The film doesn’t offer comedy as a substitute for resistance. It offers comedy as a mode of resistance—a way of maintaining human dignity and perspective even in catastrophe.

The Theatrical Frame

Lubitsch bookends the film with theatrical performances that never happen.

The movie opens with the troupe preparing an anti-Nazi play that gets censored before it can premiere. It ends with the troupe, having escaped to England, finally performing their resistance piece for a free audience.

Between these frames, the “real” events of the story are themselves structured as performance. Every confrontation with the Nazis is staged, rehearsed, costumer. The line between theater and reality dissolves completely.

This isn’t just clever structure—it’s philosophical argument. Lubitsch suggests that all political reality is theatrical, that power depends on successful performance, that the curtain between stage and world is thinner than we pretend.

If that’s true, then actors aren’t frivolous entertainers. They’re students of reality’s construction. They understand what everyone else prefers to ignore: that the world is made of performances all the way down.

A Final Thought

Near the end of the film, Joseph Tura gets to deliver his Hamlet speech properly for the first time. The pilot has escaped, the Nazis have been fooled, and Tura can finally perform without interruption.

“To be or not to be—that is the question.”

Hamlet’s meditation on death and choice takes on new meaning in this context. The actors have answered the question by choosing existence—not passive survival, but active resistance through their art. They have decided to be, fully and defiantly, in circumstances designed to annihilate them.

It’s a small moment, easily missed. But it captures everything the film believes about performance, resistance, and the power of refusing to let evil define reality.

Ernst Lubitsch made a comedy about Hitler in 1942. It was exactly the right thing to do.

My Rating: 10/10

Strengths: Perfect tonal balance, legendary performances, intellectually audacious premise Weaknesses: None that matter

If you loved this film:

- The Great Dictator (1940) - Chaplin’s Hitler satire

- Ninotchka (1939) - Another Lubitsch masterpiece

- The Producers (1967) - Mel Brooks’ spiritual successor

- Inglourious Basterds (2009) - Tarantino’s revisionist revenge fantasy