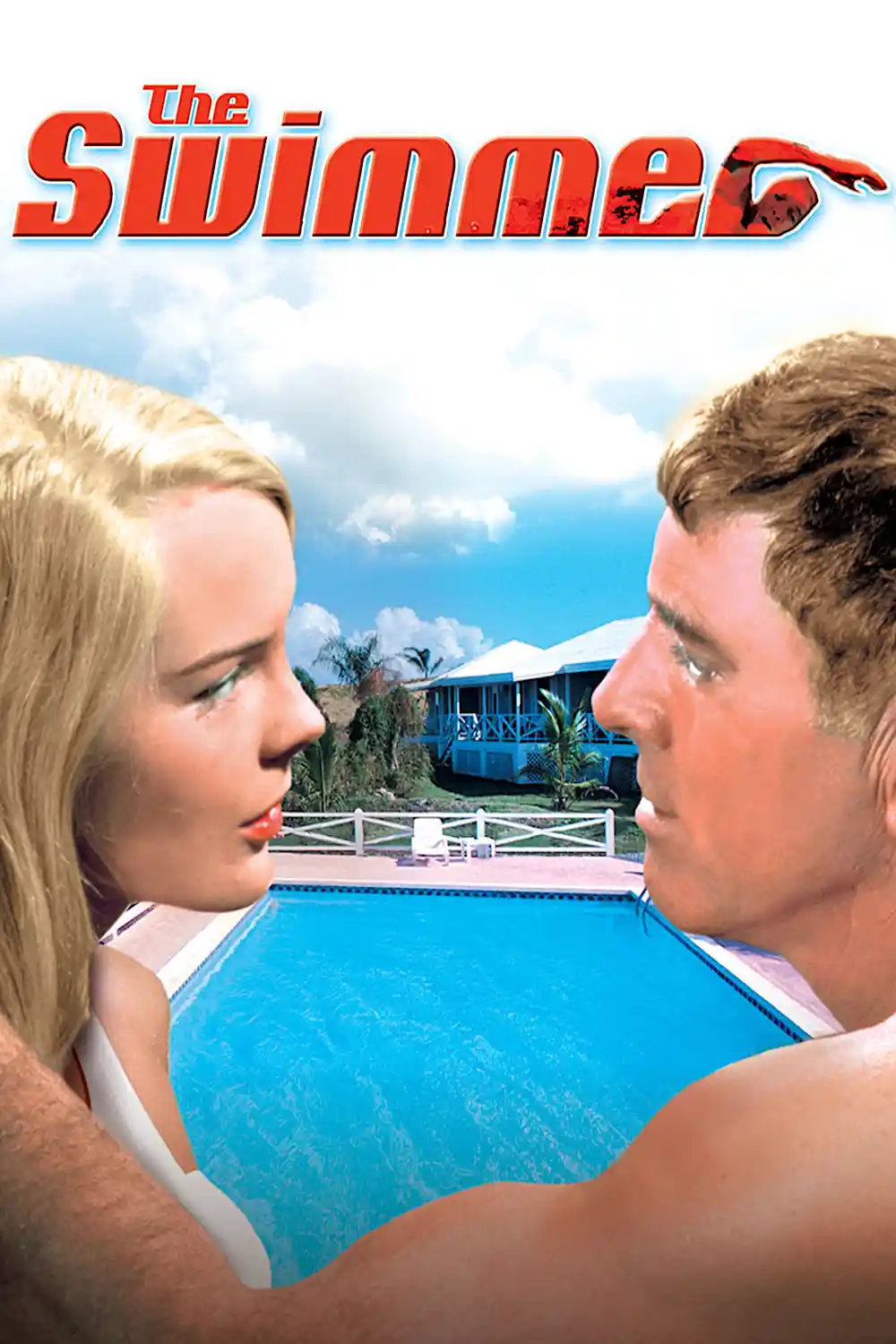

The Swimmer (1968): Burt Lancaster's Suburban Odyssey Into American Emptiness

A deep dive into Frank Perry's surreal masterpiece where Burt Lancaster swims through Connecticut backyards and confronts the hollow core of the American Dream. One of cinema's most haunting character studies.

I walked out of my first viewing of The Swimmer genuinely unsettled. Not scared—this isn’t horror in any conventional sense—but deeply, existentially shaken. Here was Burt Lancaster, that icon of postwar American masculinity, stripped down to nothing but swim trunks, and somehow that image became one of the most devastating critiques of suburban America ever committed to film.

Let me tell you something: this movie shouldn’t work. The premise sounds like a joke. A middle-aged man decides to swim home across Westchester County by hopping from pool to pool through his wealthy neighbors’ backyards. That’s it. That’s the plot. But what Frank Perry and his then-wife Eleanor (who wrote the screenplay, adapting John Cheever’s short story) crafted from this simple concept is nothing short of a suburban Odyssey—except instead of battling mythological creatures, our hero battles something far more terrifying: the truth about his own life.

The Setup: A Man, A Mission, An Illusion

The film opens on what appears to be a perfect summer day. Lancaster’s Ned Merrill emerges from the woods like some ancient god, impossibly fit for his age, bronzed and grinning. He arrives at the pool of his friends the Westerhazys, talks enthusiastically about swimming home through what he dubs “the Lucinda River” (named after his wife), and sets off on his journey.

At first, everyone seems delighted to see him. Old friends, former lovers, acquaintances—they all greet Ned with warmth. But something’s off. There are pauses. Awkward glances. Questions that don’t quite get answered.

Here’s the brilliance of Perry’s direction: he lets these moments accumulate slowly, like water seeping through cracks. You don’t immediately understand what’s happening. Neither does Ned. Or maybe he does, and he’s chosen not to.

Burt Lancaster: The Performance of His Career

I know that’s a bold claim. Lancaster won an Oscar for Elmer Gantry. He was magnificent in Birdman of Alcatraz, Atlantic City, Sweet Smell of Success. But in The Swimmer, he does something I’ve never seen him do elsewhere: he’s vulnerable in a way that feels genuinely dangerous.

Lancaster was 54 when he made this film, and he trained obsessively to achieve that physique. But here’s the thing—that perfect body becomes part of the tragedy. Ned Merrill is clinging to his physical prowess the way he clings to his delusions. His tanned, muscular form is the last armor he has against a reality that’s crumbling around him.

| Scene | Ned’s Demeanor | Reality Revealed |

|---|---|---|

| Opening (Westerhazys) | Confident, charming | Friends seem hesitant, evasive |

| The Grahams’ party | Social, nostalgic | Mentions of “troubles” brushed aside |

| Joan Rivers’ character | Playfully dismissive | Hints of financial problems |

| Shirley Abbott (Janice Rule) | Romantic, hopeful | Former mistress reveals abandonment |

| Final pools | Desperate, confused | Complete unraveling of his constructed reality |

Watch his face in the scene with Janice Rule. Rule plays Shirley Abbott, a former mistress, and when she finally tells Ned exactly what he did to her—how he promised to leave his wife, how he strung her along, how he discarded her—Lancaster doesn’t play it as a man hearing shocking news. He plays it as a man hearing something he’s been running from for years. The slight tremor in his jaw. The way his eyes can’t quite focus. It’s devastating.

The Pools as Purgatory

Perry and cinematographer David L. Quaid shoot each pool distinctly. Early pools sparkle under bright summer sun. The water is inviting, the atmosphere festive. But as Ned progresses, the pools become darker, emptier, more institutional. By the time he reaches the public pool, he’s literally swimming through masses of screaming children and chlorine—a democratized space that strips away all the exclusivity he’s clung to.

And then there’s the rain.

The weather shift isn’t subtle—Perry doesn’t do subtle—but it’s effective. The endless summer day turns gray and hostile. Ned, who started this journey looking like a bronze statue, ends it shivering, pathetic, his tan suddenly looking less like health and more like leather stretched too thin.

What Actually Happened to Ned Merrill?

⚠️ Spoiler Warning: The following section discusses the film’s revelations in detail.

The genius of The Swimmer is that it never gives you a clear timeline. Through fragments of conversation, we piece together that:

- Ned has been away for some time (years?)

- His wife Lucinda has left him

- His daughters want nothing to do with him

- He lost his job

- He lost his house

- He lost everything

But did these things happen before his swim, or during it, or is the swim itself some kind of purgatorial journey through his memories? Perry refuses to clarify, and that ambiguity is the film’s secret weapon.

My interpretation: Ned isn’t literally swimming home on a single afternoon. He’s swimming through the wreckage of his life, encountering people and places that exist in a kind of psychological geography. Each pool represents a station of his decline, and by reaching them in this order, he’s forced to confront what he’s been denying.

The final image—Ned Merrill, shaking and sobbing outside his own abandoned house, pounding on a locked door—isn’t really about a man locked out of his home. It’s about a man finally arriving at a truth he’s spent years (or one very long afternoon) swimming away from.

The Production Troubles That Made It Better

Here’s a piece of film history that fascinates me: The Swimmer had a notoriously troubled production. Frank Perry shot the original film, but the studio (Columbia) was unhappy with the result. They brought in Sydney Pollack to reshoot certain scenes, including the entire Shirley Abbott sequence.

Normally, this kind of interference destroys films. But in The Swimmer, the tonal inconsistencies actually enhance the dreamlike quality. The Pollack-directed scenes have a different texture—more conventionally dramatic, perhaps—and that dissonance contributes to the sense that Ned’s reality isn’t quite stable.

Lancaster reportedly hated the changes and fought against them. But watching the finished film now, I think the patchwork nature works in its favor. Dreams don’t have consistent visual grammars. Neither does denial.

Why This Film Was Forgotten (And Why It Matters Now)

The Swimmer was a commercial failure in 1968. Audiences didn’t know what to make of it. Was it drama? Satire? Horror? The marketing certainly didn’t help—the posters made it look like some kind of sex comedy.

Roger Ebert, reviewing the film upon release, called it “a strange, stylized work, a brilliant and disturbing one.” He was right. But “strange and disturbing” doesn’t sell tickets, especially not in 1968, when audiences were hungry for either escapism or explicit countercultural rebellion. The Swimmer offered neither. It was too weird for mainstream audiences, too bourgeois for the counterculture.

But here’s why it resonates now, maybe more than ever: Ned Merrill is the original Instagram dad. He’s the man curating his life for public consumption, maintaining a facade of success long after the substance has crumbled. He’s every finance bro posting vacation photos while his marriage falls apart, every influencer performing happiness for an audience while drowning in private despair.

The film asks: What happens when the performance becomes all you have? When there’s nothing behind the tan and the smile and the confident stroke through blue water?

The answer, Perry suggests, is that you keep swimming. You swim until you can’t anymore. And then you find yourself outside your own life, pounding on a door that won’t open.

Technical Craft: More Sophisticated Than It Appears

Don’t let the premise fool you into thinking this is some simple indie experiment. Perry’s visual choices are remarkably considered:

Color progression: The film begins in warm, saturated tones and gradually desaturates. By the final act, the palette has shifted to something almost monochromatic.

Sound design: Marvin Hamlisch’s score starts playful, almost jaunty. As the film progresses, it becomes more discordant, more anxious. The sounds of summer—children laughing, glasses clinking—give way to ominous silence.

Physical deterioration: Lancaster’s body language transforms completely over the film’s runtime. Early scenes show him bounding with athletic confidence. By the end, every movement is labored, pained. He’s aged decades in an afternoon.

My Rating: 9/10

What works:

- Lancaster gives everything he has, and it’s extraordinary

- The gradual revelation of Ned’s situation is masterfully paced

- Genuinely unsettling without resorting to genre tricks

- Cheever’s source material provides literary depth

- The ambiguity is a feature, not a bug

What doesn’t:

- The tonal shifts from the reshoots occasionally jar

- Some of the supporting performances feel dated

- The pacing in the middle section drags slightly

If You Liked This, Try:

- The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) — Another athletic journey as psychological excavation

- Five Easy Pieces (1970) — Jack Nicholson’s working-class parallel to Ned’s bourgeois breakdown

- The Graduate (1967) — Same era, same critique of American emptiness, different generation

- Falling Down (1993) — A spiritual sequel of sorts, with Michael Douglas walking through L.A. the way Lancaster swims through Connecticut

The Swimmer remains one of American cinema’s most peculiar achievements. It’s a film that uses a ridiculous premise to reach profound truths, a star vehicle that dismantles its star, a summer movie that leaves you cold. If you haven’t seen it, seek it out. And when you do, pay attention to that final image: a man outside his own house, unable to get in, having finally arrived at a destination he’d been fleeing his entire life.

Some journeys home are actually journeys away. Ned Merrill just didn’t know it until the water turned cold.

References

- Ebert, Roger. “The Swimmer” review, Chicago Sun-Times, 1968

- Dempsey, Michael. “The Swimmer: A Re-evaluation,” Film Quarterly, 1991

- Cheever, John. “The Swimmer,” The New Yorker, 1964

- Lancaster, Burt. Interview excerpts, American Film Institute archives

- Buford, Kate. Burt Lancaster: An American Life, Da Capo Press, 2000

- Thompson, David. “Drowning in Suburbia,” Sight & Sound, 2014